Indigo, the blue gold

Who doesn’t love blue? I do and I think living by the sea has definitively some impact on how I see blue. Each walk along the coast reveals a new palette of colours. Imagine my excitement when I discovered years ago that I could produce a blue from a natural source! It feels like a magical process when you dip the fibres into an indigo dye vat and then see how the colour changes upon coming into contact with the air, turning from a yellow green to a deep blue colour.

While indigo is an exciting subject, it is also a wide ranging. It encompasses different plants and some different processes. Writing about this amazing natural blue colour is based on my experience, on what I learned from specialised courses (i.e. Couleur Garance) and books from authors I trust. As you know by now, working with plant based colours takes a lifetime of practice and experience. I am happy to share with you what I know and hope you’ll find it enjoyable. On a related topic, I’ve also included a brief story of denim at the end.

Indigo is the most colourfast of the natural dyes and ages beautifully.

WHAT ARE THE PLANTS

They are many plants that are used to make indigo. There are probably ten of them that can be used for dyeing. Here are some of the most commonly used :

Indigofera tinctoria. Indigo powder comes from the leaves of the indigo plant, one the oldest dyes from India. It comes from hot regions. Cultivation of this plant started thousands of years ago, and spread throughout Asia, American and Africa.

Isatis tinctoria knows as Pastel or Woad, a paler variety from Europe. This is a biennial plant. The first year the leaves can be harvested and used to extract the pigment. The second year the plant grows up to 1.5m high and flowers. It is the only indigenous to Europe.

Persicaria tinctoria , the Japanese Indigo from East Asia and China. It is an annual plant which grows quickly, up to 60 cm high.

Indigofera Suffructicosal from South and Central America,

Strobilanthes cusia from south east Asia and

Philenoptera cyanescens from west Africa.

When I first started to use natural indigo, I got some Indiogera tinctoria. I now source my indigo pigment from www.lechampdescouleurs.com, an organic dye farm in the Provence, France, where two sisters started to grow dye plants a few years ago. Michel Garcia, who invented the 1-2-3 indigo vat process, brought back seeds from Sapporo island, Japan, and since then they produce and extract a large amount of beautiful organic indigo. They prepare this natural indigo from fresh leaves using organic and sustainable farming. The blue colour obtained is rich and deep.

Below are: Indigofera tinctoria, Persicaria tinctoria, Woad (pastel) flowering the second year, Woad leaves only the first year:

SOME HISTORY

Indigo has so much history associated with it. It is one of the most ancient and scarce natural dye colours. A recent archaeological discovery shows that some cotton fabrics were dyed in blue in Peru 6,000 years ago.

Here are some of the historical facts among many:

The name indigo may come from one of the oldest civilizations in the world, the Indus, who also gave their name to the Indus Valley in India. India was the earliest major centre of natural indigo production. It was exported in small cakes in 300-400 AD.

The Greeks and Romans considered it a precious ‘mineral’. The ancient Egyptians and Romans used it as pigment for making paints, medicines and cosmetics.

Marco Polo, in the 13th century, returning from his voyage in Asia informed all that it was a plant based product.

After the 12th century, blue became an aristocratic colour. It was for ex. the official colour for the French king’s coat of arms.

Blue extracted from woad (pastel) was used by painters in 12th Century to colour the Virgin Mary’s clothes.

It was also used in medieval manuscript illuminations.

Woad, the pastel European blue, was the only source of blue dye in Europe until the end of the 16th century when other indigo plants were introduced to Europe. Pastel has a lower concentration of indigo, so local woad industries were threatened when indigo was imported from India in large quantities. There are some interesting historical facts about this plant but I’ll leave that to another blog post.

Napoleon’s Grande Armee consumed around 150 tons per year as a uniform dye.

In the 19th century indigo was known as the ‘blue gold’ and used as a trading commodity, due to it is long lifespan and rarity.

When the colour was synthetised in 1870 by the chemist Alfred Bayer, the indigo market collapsed as manufacturers turned to the synthetic version. This was similar to what happened for red, obtained through madder root (see previous post). The growth of the fashion industry in the 19th century and the industrial revolution, with the popularity of denim, required large quantities of blue dyed cloth. The replacement of natural by synthetic indigo grew.

USING NATURAL INDIGO

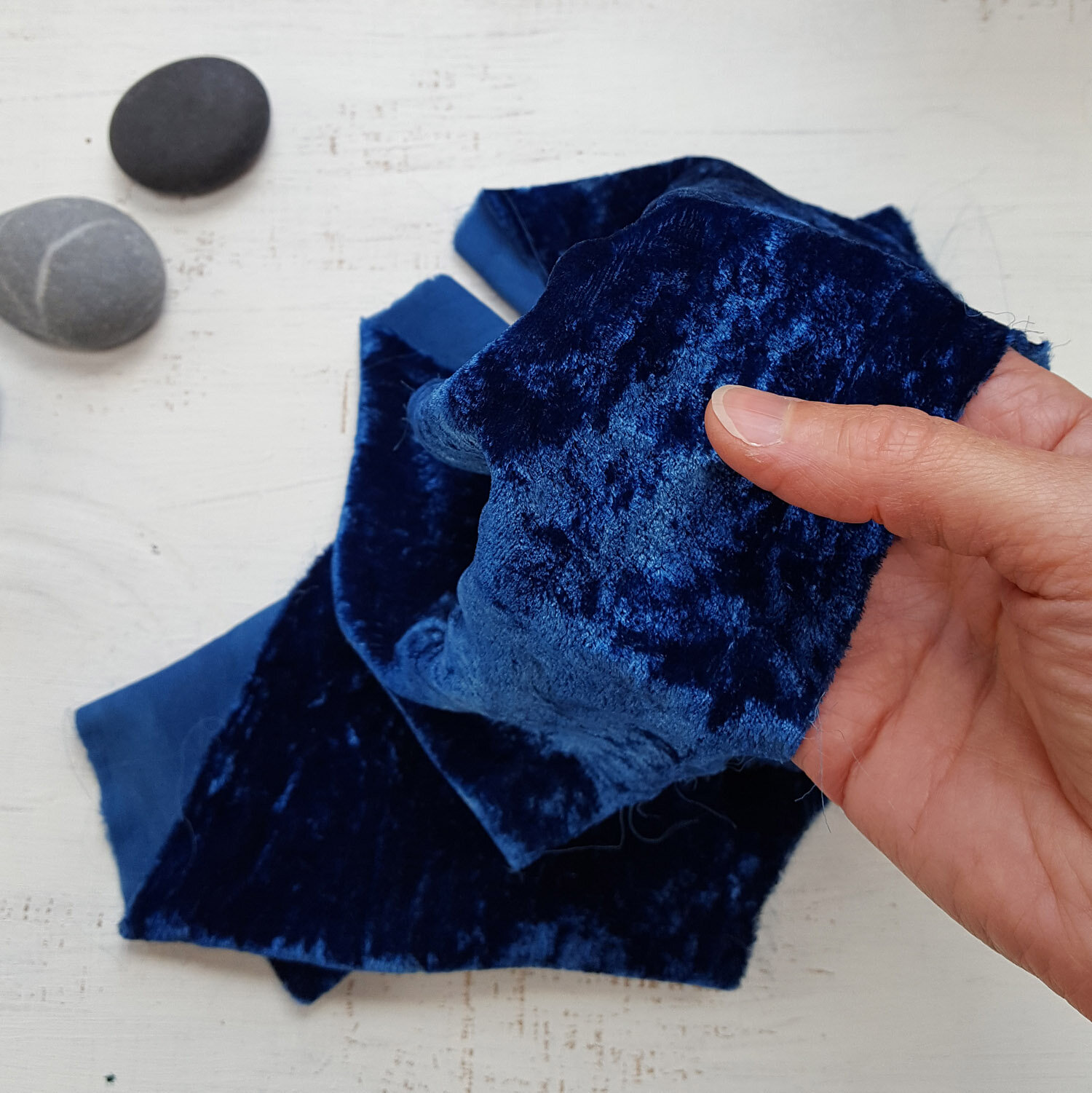

Generally, indigo is sold in the form of powder or ‘cakes’, if you don’t make it yourself from the leaves. Indigo from plants doesn’t require any mordant on the natural fibres before dyeing. It can be used on all natural fibres, cotton, silk, linen, kozo ,hemp, flax, wool etc. Traditionally, the fabric was dyed directly in fermented baths. The method to obtain that beautiful blue is far from simple as the plant doesn’t contain actual blue pigment but only its molecular precursors, indicant and indoxyl. These are soluble and colourless.

HOW:

Indigo comes from fermented plant leaves. Extracting indigo requires a complex fermentation process, which is labour and time intensive. Indigenous cultures have used a formation vat technique for centuries which is very difficult to keep balanced and in a dyeable state. After the indigo has been extracted from the plant, it is not water soluble. The vat process allows the indigo to become soluble and usable.

Michel Garcia, a French chemist and natural dyer, developed a simplified method using an easy process and only three natural ingredients: slaked lime, fructose sugar and indigo. This technique has been selected by many dyers and is the only method that I use. It is both safe and easy.

Indigo dye provides ranges of blue shades, from clear to dark, with good light and wash fastness. It turns from an oxidised state (insoluble blue pigment) to a reduced state (soluble, greenish yellow pigment). This allows it to be fixed on the natural fibres before being oxidised again, developing the colour to blue. A natural vat using fructose plus hydrated lime plus indigo pigment is used for this process. As previously mentioned, this is the process I use. Another type of organic vat requires iron, or henna, or reduced fruits.

The indigo vat uses plant sugars to rapidly start the reduction, beginning in just a few minutes. The vat is usually ready for use after 12-48 hours. It is relatively easy to maintain and, with care, can be used for long periods of time. I have two vats that I have started over a year ago and they are still going, once I rebalance them. The indigo vat requires high alkalinity (high PH) to function well.

On a side note, I sometimes come across people who are still making their indigo vats with hydrosulfite as a reducing agent, which is toxic! The above 1-2-3 method is simple, organic and works beautifully!

Indigo can be used in combination with other plants such as madder roots, pernambucco bark, buckthorn… giving beautiful colours. See below a few examples:

The story of blue denim

Levi Strauss founded the first company to manufacture riveted blue jeans. He imported fabric called ‘denim’ from Europe which was dyed uniquely with indigo. The origin of the word denim is still not clear. It is possibly derived from the French ‘serge de Nimes’ fabric, made with wood and silk waste from the Nimes area since 17th century. However, the name is also associated with a fabric made of linen and cotton produced in Bas-Languedoc and exported to England. There is also a wool sheet produced between Provence and Roussillon and called in Occitan de nim, so it could be as well the origin of the name.

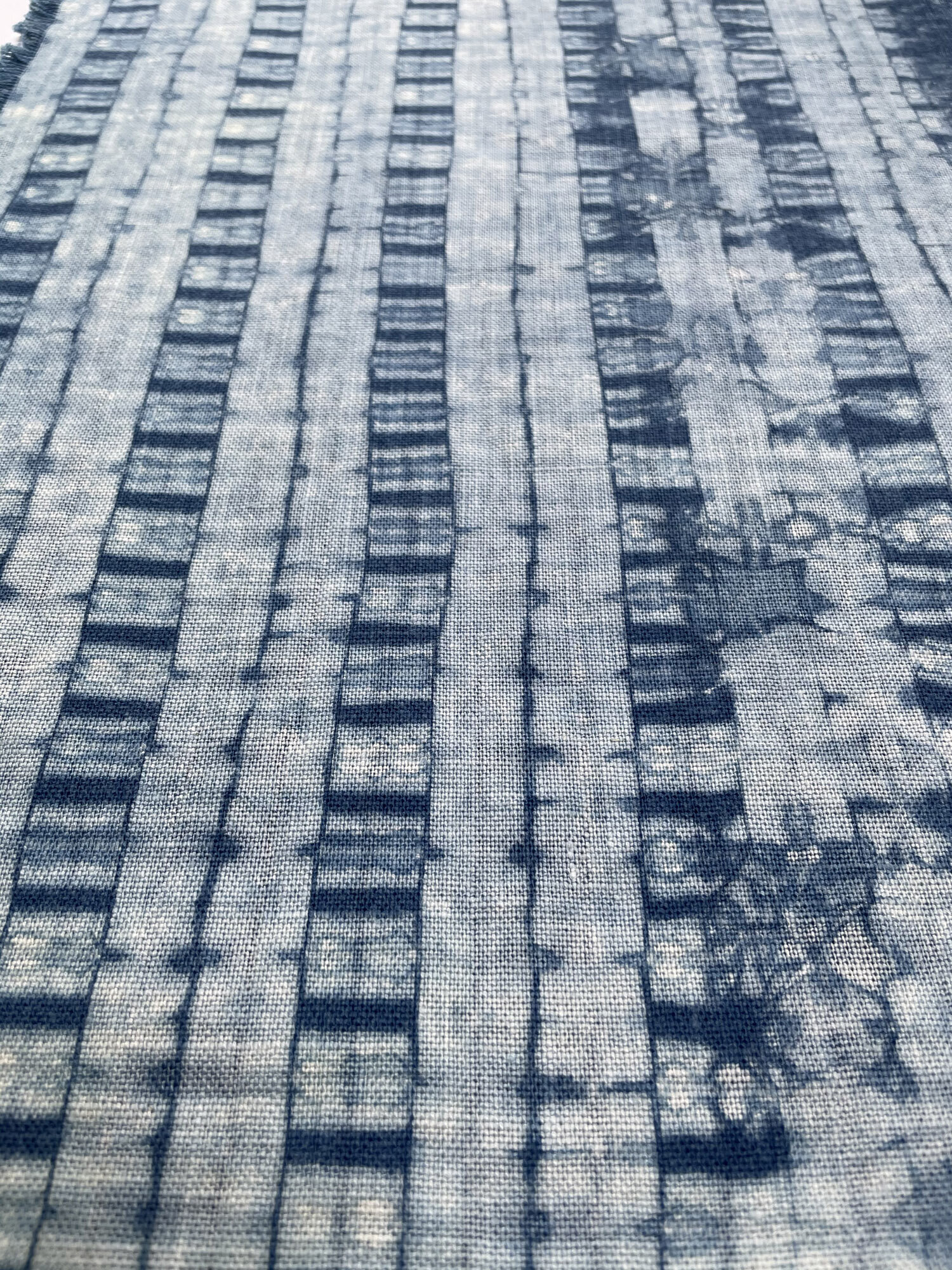

Since the beginning of the 19th century, in England and US, denim was characterised as a strong cotton dyed with indigo. It was used principally to make clothes for manual workers, labourers, and slaves. Around 1960 Levi Strauss, who had been using rough tent fabric to make trousers and overalls, replaced it gradually with denim. Blue jeans were born. As it was still too thick to fully absorb the dye correctly, its uneven colour became its success. The plant based colour became lighter as worn. Decades later when the natural blue indigo became a synthetic blue, the jeans companies retained the distressed and faded look by bleaching, stone washing, the fabric.

This is not by any means the full story of the indigo, as there are so many uses all over the world and history attached to it. I hope it gives you a summary and maybe a taste for it. I will probably write another post about pastel (woad) that I am growing at the moment.

Below I have included some books and websites I would recommend, if you want to go deeper.

Thank you for reading, I’d love to hear your thoughts and if you are a blue lover :-)

Until next time,

Fabienne x

Books and sites: Guide des teintures naturelles (Marie Marquet) - Teindre avec les plantes (Elisabeth Dumont) - The Art and Science of natural dyes (Joy Boutrup & Catherine Ellis) - The Secret Lives of Colour (Kassia St Clair) - www.couleurgarance.com - www.lechampdescouleurs.com